Have you ever faced someone in training who just had a knack for getting out of bad spots?

You’d catch them in situations that you were sure you would be able to finish them in, like a tight armbar or a deeply-sunk rear-naked choke, but no matter what, they would find a way out.

You’d squeeze, pull, and wrench against their limbs, but nothing did would get a tap from them.

And time and time again, this person managed to escape from your grasp and slip out from what you thought was certain victory on your end.

How do they do it?

It turns out there’s a little-known secret to developing an impenetrable submission defense.

Our example training partner above has a simple but game-changing skill in jiu-jitsu – they know how to think mechanically.

Thinking mechanically is the number one fastest and most effective way to developing impenetrable submission defense across the board and improving your grappling as a whole.

Thinking mechanically involves asking yourself two simple question every time your opponent attempts a technique on you:

1. What is my opponent trying to do?

and

2. How do I stop it?

I don’t mean that in the obvious sense.

If you’re under someone’s mount and they’re pulling your arm across your chest, clearly, they’re trying to armbar you – but think about the mechanics behind the technique they’re attacking with.

Using the armbar from mount as an example, think to yourself:

- What’s keeping you there?

- What’s being threatened?

The answers are:

- Your opponent’s leg across your head. This is what prevents you from simply sitting up and turning into your opponent.

- Your arm. Or more specifically, your elbow joint

Being aware of these two underlying mechanics of the technique allows you to come up with an effective solution to defending and escaping the armbar.

How I Learned To Escape The Armbar

If there’s one technique on the ground that judokas are known for, it’s the armbar. Because you only get 30 seconds to work on the ground, judokas need a submission that’s fast, powerful and easy to apply.

Watch this if you want to see for yourself.

One of the guys at my home gym is a judo and BJJ black belt, and sure enough – his armbar game is tight. He regularly taps out everyone from white to black belt, seemingly in the blink of an eye.

One of my proudest moments in my development as a grappler was when I first escaped his armbar. At first, I thought this was just a fluke until I did it multiple times in the weeks following.

I was proud beyond words. As far as I knew, no one could escape this guy’s armbar when he had it locked in.

And the way I did this was so simple, I still find it hard to understand why I don’t see it being used more often.

Since I knew that, in an armbar, my opponent’s leg on my head was the only thing keeping me trapped in the position, I could escape if I found a way to move his leg off my head just long enough for me to sit up.

Of course, that was easier said than done, since my opponent was trying to break my arm at the same time. But after playing around with different defenses to the armbar, I realized that there was a way to protect my arm and move his leg off my head at the same time.

I call this one the figure-four push:

- Use a figure-four/”rear-naked-choke” grip to protect your trapped arm. This protects your trapped arm leaves your other arm free to move around.

2. Keeping the grip intact, use your free arm to push your opponent’s leg off your head (combine with a bridge for maximum effectiveness)

3. Once you’ve cleared the space for your head to come up, explode and sit up into your opponent’s guard

To understand jiu-jitsu from a mechanical perspective, it helps to have a basic understanding of human biology as it relates to breaking bones and choking people unconscious.

Joint Locks & Chokes: Understanding the Mechanics

Nearly all grappling submissions fall into one of two categories: joint locks and chokes.

Joint Locks: The Art of Breaking Limbs

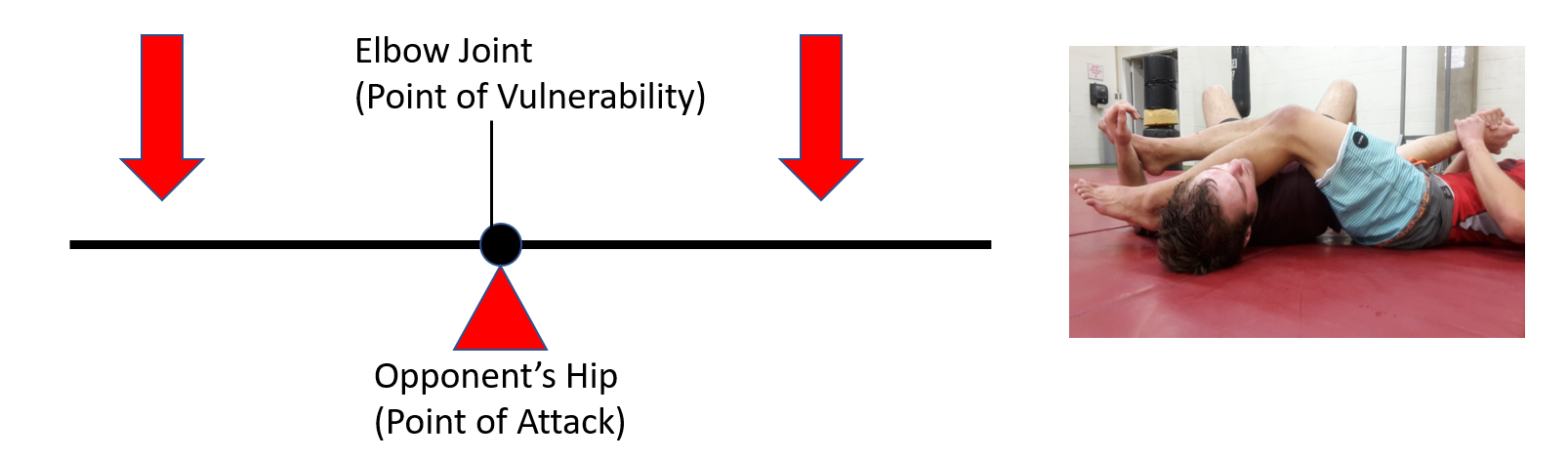

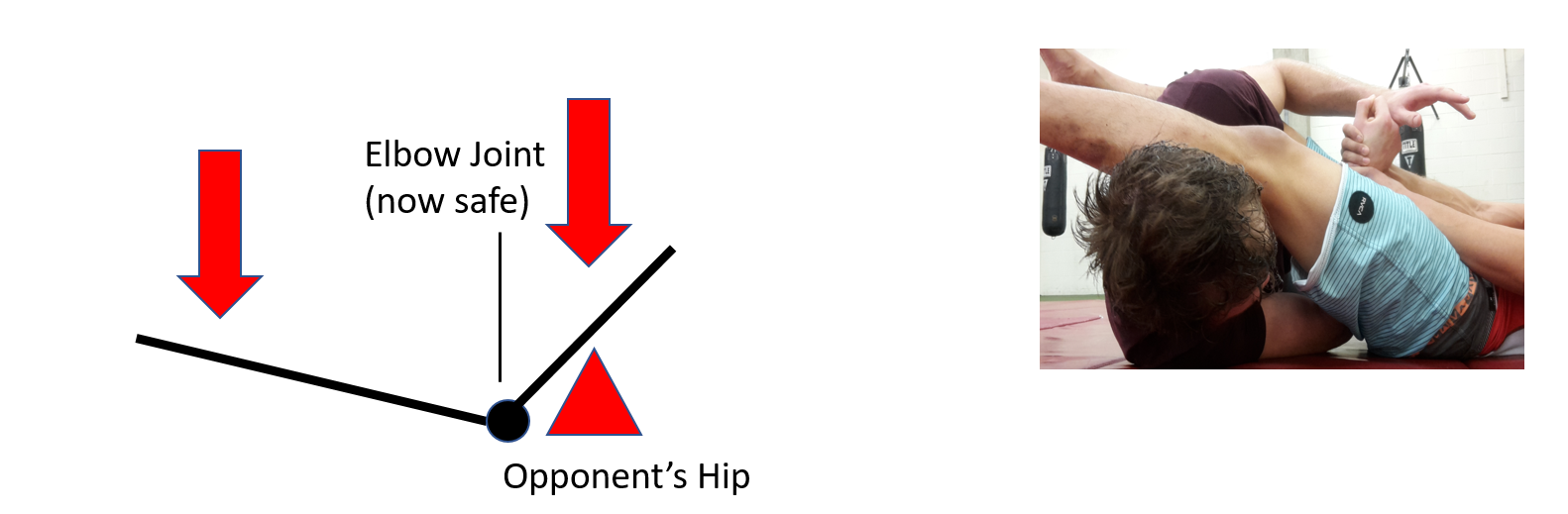

Joint locks work by threatening to break limbs at the joint (the intersection of two different limbs), by holding the limb in place while applying pressure to the joint.

For example, an armbar threatens the elbow joint, which is the intersection between the forearm and the upper arm.

This is important to realize, as the key to defending against the armbar is simply to move the point of vulnerability (the elbow joint), away from the point of attack.

This is why simply rolling into the attacker while shrugging your arm in is a very effective escape to an armbar that isn’t quite tight enough.

Chokes

There are two kinds of chokes in jiu-jitsu: blood chokes and windpipe chokes. Let’s go over the mechanics of both.

Blood chokes work by cutting off both of your carotid arteries.

Run your fingers along the sides of your neck right under the chin and you will feel a vertical vein on each side where your pulse jumps out at you. Those are the ones.

They’re responsible for delivering blood to your brain and if suppressed simultaneously, will result in you falling unconscious, or “going to sleep” after a certain amount of time (usually within 10-30 seconds).

If you apply pressure on these two arteries with your thumbs, you’ll notice that within ten seconds or so, you start to feel slightly light-headed. Let go (of course) when this happens, but it should give you a good idea of how blood chokes work.

You’ll notice that you can still breathe while experiencing this sensation – that’s the beauty of blood chokes. They allow you to choke someone unconscious without restricting their air supply.

Often someone caught in a clean blood choke (one that doesn’t restrict their windpipe) isn’t even aware that they’re being choked out until moments before they go unconscious. That’s why you hear about people “going to sleep” when they roll.

Chokes that fall under this category are:

Triangle chokes, Arm-triangle chokes, Anaconda chokes, D’arce chokes (when applied correctly), Rear-naked chokes (though these often become windpipe chokes as well)

Windpipe chokes work by cutting off your windpipe at the front of your throat.

This directly interferes with your ability to breathe, and as you can imagine (or know from experience), is quite painful. Most people who tap to windpipe chokes do so from the pain. It’s very rare that someone actually goes to sleep from a windpipe choke.

Chokes that fall under this category are:

Most guillotines, Ezekiel chokes, Peruvian neckties

Applications

Triangle Defense & Offense

The triangle is (in my opinion) the king of blood chokes.

When you lock in a triangle, you’re using your legs and one of your opponent’s own shoulders to compress their carotid arteries. If done right, it should result in your opponent falling asleep or tapping out without ever struggling to take a breath.

That is, a good triangle choke achieves its effect by compressing the carotid arteries on the sides of the neck without ever becoming a windpipe choke.

The key to effectively defending against a triangle when you’re caught in one is to remove the sources of pressure on your carotid arteries (your own shoulder and your opponent’s thigh).

To buy time when I’m caught in a triangle, I’ll curl my trapped arm and press my elbow into my opponent’s thigh, trying to push it down as if I were trying to touch my elbow to my own leg.

The goal here is to create as much space between my shoulder and the side of my neck as possible, freeing up the carotid artery on that side of my neck and buying me at least a few seconds of free time.

From there, I’ll work to wrap my arm around my opponent’s thigh and lock my hands together underneath. This creates a stable position from which I have ample space between my shoulder and neck, and from there I can work on escaping.

Note that these are both survival tactics for a worst-case scenario. As I’m sure you’ve heard before, the best way not to get tapped out by a triangle is to not get caught in one.

Offense

The flip side to this is that if you’re attacking with a triangle, your goal is to close that gap between your opponent’s shoulder and the side of his neck.

This is why squeezing your legs together and pulling down on the head is an inefficient way to finish the triangle.

A much more effective way is to turn your body so that you are perpendicular to your opponent and rotate his shoulder into his neck using your legs.

As the saying goes, ask me how I know.

Defense to the Standing Guillotine

Standing Guillotines

One of the problems I encountered a lot as a white belt was that I when I shot for takedowns, I would always run into guillotines and have no idea what to do. I couldn’t reach their legs because my opponent would keep their hips back, and the pressure on my throat was so tight I’d tap almost right away.

Eventually, I realized that if I turned to the side, I could remove the pressure on my throat because the blade of their forearm would no longer be perpendicular to my windpipe.

At that point, my body would be perpendicular to my opponent’s, and I would have a tight underhook on the side that they weren’t trying to guillotine me on.

I later combined this with a takedown similar to the Tani-Otoshi from judo, and was able to land in side control and secure an arm-triangle a very high percentage of the time.

That’s the power of mechanical thinking.

By thinking about what actually made the move work, I was able to reverse-engineer the technique and develop a counter that actually let me attack with my submission.

How You Can Use Mechanical Thinking

Now that you know how each of the submissions you’ve been taught work on a mechanical, you can use this information to your advantage.

How?

Mainly, realize that the submissions you know only work if they apply pressure to specific points on the body, often simultaneously.

We know that:

- Joint-locks only work if pressure is applied at the joint while the limb is held steady

- Blood chokes only work if consistent pressure is applied to both carotid arteries on the sides of your neck (sometimes you can get away with one, but rarely)

- Windpipe chokes only work if pressure is applied to the front of your throat

Those four lines might be the most lines you read about jiu-jitsu if you can apply the information effectively.

Once you start seeing submissions and submission defense from the perspective of applying or removing points of vulnerability, you can become the guy or girl “who is weirdly difficult to submit” or tighten up your own offense and improve your finish rate.

Knowing how to think mechanically is like hacking the world jiu-jitsu. It opens up a world of possibilities in your defense and offense, as you now understand the principles behind what makes a technique successful or not and can use them to develop your own effective solutions to the problems presented to you on the mat.